Ghetto Theresienstadt

דף הבית » Ghetto Theresienstadt

Ghetto Theresienstadt 1941 -1945

Theresienstadt (Terezin in Czech) was founded in 1780 as a fortress town to the North of Prague and was intended for a population of 7,000, half of being soldiers. After Czechoslovakia was occupied by Germany (March 15, 1939), a ghetto was established in Theresienstadt on November 24, 1941. Allegedly for Czech Jews, it was, in fact, a concentration camp and a staging point to the death camps in Eastern Europe.

The Ghetto in numbers:

At its peak (September 1942) 58,491 prisoners were crowded into the ghetto and it functioned until its liberation by the Russian army on May 8, 1945.

Out of 160,000 prisoners from Czechoslovakia, Germany, Austria, Holland, Denmark and other countries that passed through Theresienstadt between 1941 and 1945, about 35,500 died in the ghetto from hunger or disease. About 90,000 were deported from there to extermination camps and out of these, about 4,800 survived. On the day of liberation, there were about 30,000 Jews in the Ghetto.

Of the 12,121 Jewish children born in the period 1928-1945 and sent to the Theresienstadt Ghetto – whose future was uppermost on the mind of the Jewish leadership – 9,001 were deported to extermination camps in the East, out of whom only 325 children survived.

When emigration became impossible, the leadership of Czech Jewry headed by Jacob Edelstein supported the establishment of the Theresienstadt ghetto in October 1941. Edelstein, appointed as “Jewish Elder” of the ghetto, believed in “rescue through work” and hoped that concentrating Jews within the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (today the area encompassed by the Czech Republic) would prevent their deportation from the ghetto and keep them safe until the Allies would win the war.

The difficult conditions in the ghetto were in sharp contrast to everything that the Germans had promised. In January 1942 the illusion was shattered, when transports from Theresienstadt to the East commenced and 16 Jews whose crime included the sending of letters to their families, were executed by hanging.

The Theresienstadt Ghetto had a special character – the Germans wanted to turn it into a ghetto for old and deserving people from Germany and Austria and use it as a “model ghetto” and a tool in their propaganda efforts. Despite the difficult reality in the ghetto, the Jewish leadership succeeded, up to a certain point in maintaining services of health, food distribution, living quarters, and work organization as well as fostering cultural and sports activities and taking care of the education of children and youth.

Towards a visit to Theresienstadt by a delegation of the International Red Cross on June 23, 1944, the “ghetto beautification” operation was carried out. Under threat and heavy pressure, the Jewish leadership and the prisoners participated in the German deception, hiding the real conditions in the ghetto – hunger, overcrowding, diseases, high mortality, and the transports. After the visit, in the summer of 1944, a propaganda film was shot in the ghetto thereby continuing the deception. After the filming, about 18,000 ghetto prisoners were deported in September and October 1944 to Auschwitz – most of them perished. Towards the end of the war in 1945, the ghetto became the destination for “death marches” for many thousands who were brought from extermination camps in Eastern Europe.

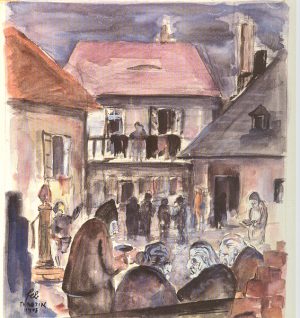

Courtyard of the Old People, Ferdinand Bloch

Newsletter Sign up